Soft Shell Crabs and Wonder Bread

Lost Flavors and the Chesapeake Bay

In his Monkey Wrench Gang, Edward Abbey comments pejoratively about people “munching on mayonnaise and Kleenex sandwiches of Wonder, Rainbo and Holsum Bread.” For current generations raised on versions of whole wheat, the uniform blandness of 1960s white bread must seem strange. Indeed, much like brand loyalty regarding gas stations—having a Texaco card narrowed fuel options—back then people also committed to their bread, even if it was all of a homogeneity that defied differentiation. Kirkwood Avenue in my Atlanta neighborhood was once the commercial district of the town. Every few houses on the western end have attached small brick former storefronts. There are conflicting reports from neighbors who lived here back then. Either each store sold more or less the same items—mostly groceries and necessaries—or they sold mostly the same things but were distinguished by their bread affiliation: “Wonder, Rainbo and Holsum,” or perhaps Sunbeam or Merita. Each slice almost a perfect square with an absolutely uniform (and easily removable) crust and a blindingly white interior of equally uniform cells.

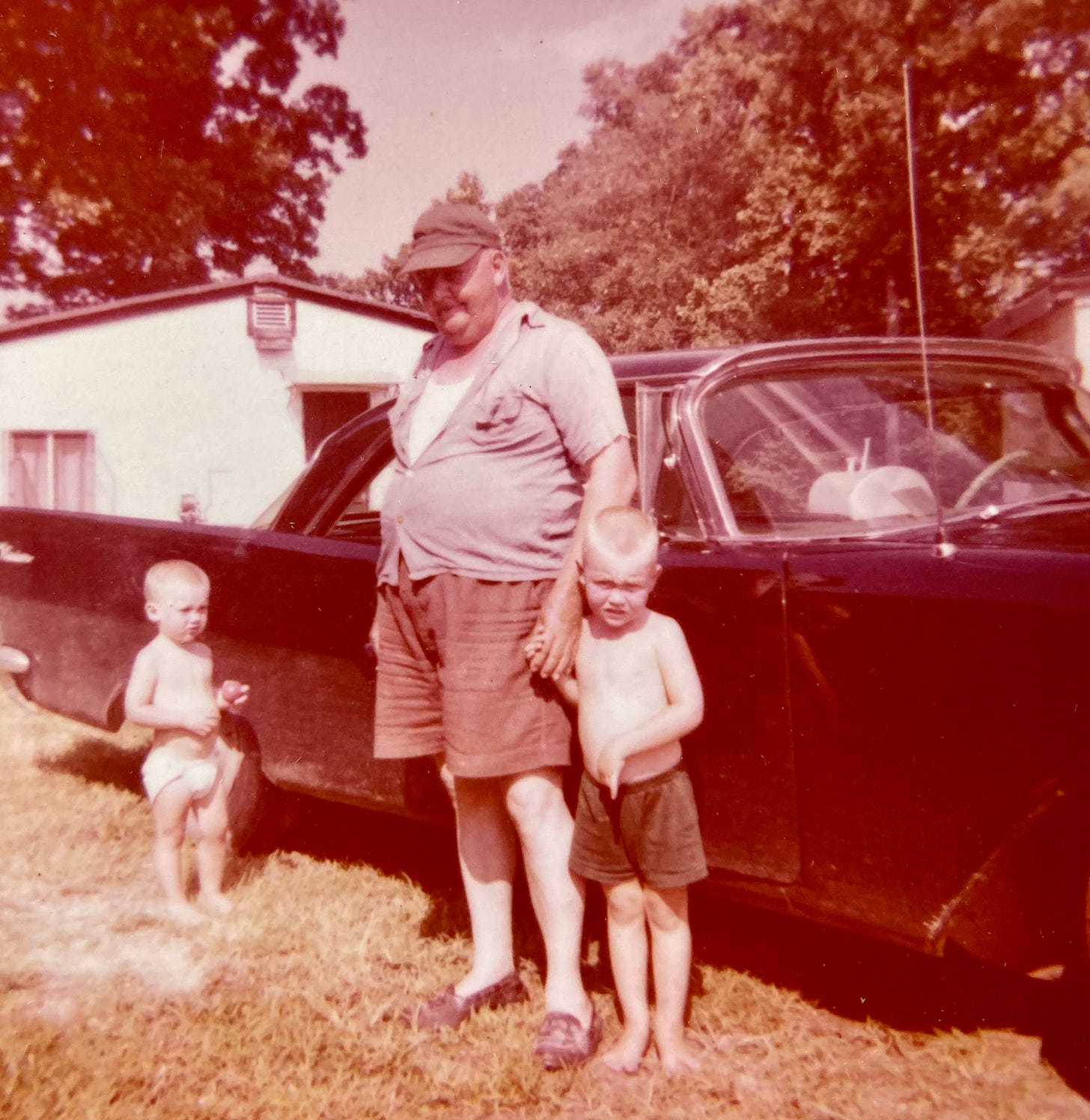

I can still see the loaves of Wonder at the fish camp. LC Rocchiccoli— affectionately called Rock—looms large in the imagination of my early years. A large, very large, very pale (even pasty) man in a tshirt and Bermuda shorts. Close cropped thin hair, a face generously described as pudgy, but possessing the brightest eyes I have ever seen. The moment yours met his an instant connection occurred. I was no more than 7 and immediately recognized I was in the presence of a large soul (I have to admit in the 60 years since I have met few large souls). His fish camp was on Meachim’s creek, a tributary to the Rappahannock river—a simple cinderblock structure with a front porch and rudimentary facilities. It was by anyone’s standards rustic, but to me and my brother it was a palace. Time on the river was not just fishing on a deadrise boat, it was exploring on foot the sandy watershed of the creek or going out in my father’s little speed boat— a small fiberglass craft with a white hull, red front deck, and a Johnson outboard. Back home in the valley, he would pilot it on a small stretch of the Shenandoah river above what is now a washed-out dam. Everyone would waterski trying to avoid overhanging trees on that narrow strip. I dimly remember being 4 or 5 standing between his knees while he skied a water disk behind that boat, making those tight whipping turns, blurring my vision and tightening my guts. Meachim’s creek has a clearly marked channel entrance off the river, but, at least back in the 60’s, you could cross into it over a closer sand bar at high tide. One day out on the river, we were speeding back to make the shortcut. From a distance, I could see clearly the water lapping the exposed sand as the tide was running out, but Dad simply removed the kickback pin from the Johnson, pushed the accelerator to the limit and after an initial thud, we found ourselves airborne, sailing over the bar and into the calm waters of the creek, then slowly motoring to the dock to tie off.

One of Rock’s best friends was BB Bly, a good friend of our family who lived on a farm in the Shenandoah Valley. I remember his place fondly— my father boarded his horse Lady there and BB’s daughters cared for her. Once every year, BB would order at least a bushel of lobsters from Captain Crawford’s Lobster House in Kittery Maine (no relation that I know of). They would set up a huge steamer in his back yard, and we would all dive into as many red bugs and ears of corn as we could eat. Faces dripping butter after inhaling claw meat and tails, we would pile the bodies on a platter in front of BB where he would meticulously pick them clean—he knew his way around a lobster. Seafood arriving in the valley back then occasionally included a bushel of oysters. My father had these heavy red rubber gloves and his personal oyster knife and would stand at our kitchen sink shucking rapidly, while my brother and I stood on either side with mouths open like baby birds where he would flick the occasional oyster down our expectant throats. But in the summer, we would all gather at Rock’s.

Paul Metcalf’s wonderful but largely unread Waters of the Potomack quotes a colonial journal on the bay fishery: “For fish, the Riuers are plentifully stored, with Sturgion, Porpusse, Base, Rockfish, Carpe, Shad, Herring, Ele, Catfish, Perch, flat-fish, Troute, Sheep’s-head, Drummers, Iarfish, Creuises, Crabbes, Oisters, and diuerse other kindes ….” Pollution in the latter half of the 20th century has ravaged the fisheries even as the bay remains one of the most seafood productive body of water in the country. Because of water pollution in the 60s, the shad runs were significantly diminished but not finished. For my father, the spring Potomac run always brought a cooler of shad roe from old friends. I well remember the pinkish eggs encased in a thick veined membrane, pairs of long lobes that were singularly unappetizing to a young person. Some historians attribute the victory of the American colonial troops over Great Britain to the remarkable plenty shad provide people in the bay. Apparently Washington’s troops were sustained at Valley Forge with Potomac shad, dried and stored by watermen. Cooking shad roe is an art as the individual eggs pop, making quite a mess. My father, who generally was not a cook, would take over the stove, heating a frying pan with bacon grease and wrapping the lobes of roe in wax paper, frying them up like little presents for us. We would each get one, steaming from the pan, expressing flavors I have never since experienced.

Early in the morning at Rock’s camp, after bacon and eggs, we would board an old Chesapeake deadrise with a canvas canopy over the open deck and make our way out into the river. I always wondered how the boat could be guided without a wheel, with what to my eyes was just a single stick amidships next to the engine compartment, but bay watermen can maneuver these work boats with remarkable precision. We’d make our way into the broad expanse of the Rappahannock, soon finding ourselves bouncing beneath the rusty steel trusses of the Robert O. Norris Bridge. Although we could pass beneath pretty much anywhere, we always headed to the midpoint —the space open for the largest vessels. Back then there were some pleasure boats, a few sail, but mostly there were other deadrises. This was a working river and, depending on the season, the watermen were fishing, crabbing or tonging oysters. Sometimes we would encounter the menhaden ships— fairly large smelly craft with small fleets of net-tending boats catching tons of menhaden (also called alewives) for use as fertilizer, fish oil, animal feed, as well as bait for the crabbers. Not far from the bridge was a then-abandoned fish factory built to process the menhaden. We would visit the old piers there with a scoop net to gather the crabs that attached themselves to the pilings. It was there that I first saw a living, growing sea sponge. Out on the deadrise we would spend the morning fishing with simple rod and reel for rock fish (striped sea bass) though I don’t remember eating any of our catch (my father loved his seafood, but confined his appetite to shellfish).

You would think the river would be a sheltered place, but its waters get rough. Given that, there is no boat more reassuring than a Chesapeake deadrise. Modeled on the Skipjack—wide beamed sailing boats designed for oystering—the deadrise was the workboat of the bay. Wooden, usually with a small cuddy cabin in the bow, they have a large working deck, diesel engine amidships, broad of beam with a fairly shallow draft. After all, working crabs requires time on the shallows of the sand bars. In the years when I visited, the banks of the tributaries were littered with the rotting hulks of old deadrises, marking the decline of the fisheries at least as practiced by lone watermen. But the ones still in operation always had bright white paint and exuded a sense of security (which belies the mood their name invokes). The highlight of a fishing day was the return to Meachim’s creek. We would run up the hill from the dock after first looking into the floating holding pens— one containing the day’s catch of hard crab taken from the pots at the end of the pier, and the other sometimes holding busters and peelers—our soon-to-be soft shell crabs. Regarding those crustaceans, my father always said “if god made anything better, he kept it for himself.” Blue crabs molt every 50 days during the growing season. They nearly-hibernate in the winter, bedding down in the mud mid-channel with the pregnant females all the way down at the mouth of the bay to winter in water with salinity high enough to nurture their egg casings (crabs mate continuously for 6-12 hours before decoupling). Watermen have a well-developed sense of when a caught crab might be a buster and will set them aside in water-filled buckets for a different market than the barrels of sooks (mature females) for the picking house and Jimmies (large males) for the steamed-crab restaurant trade. Early in the crab industry, Marylanders pioneered techniques to scale production of soft shells, but the watermen all over they bay had their own techniques. A soft shell is only soft for a day or so, then it is paper, and by 72 hours a almost new hard-shell. In the 1990’s 95% of all soft shell crabs consumed in the US were from the Chesapeake. Lots of people have been served paper shells masquerading as soft in restaurants only to be disappointed, but as we well knew in Rock’s camp, a newly shed peeler is a gift from heaven.

The vast majority of soft-shell crabs come from the Chesapeake, and the principle harvesters there live on Tangier Island, an (increasingly) small bit of land in the middle of the Bay just on the Virginia side of the Maryland border. It is a storied place, sometime home of picaroons (pirates) in the Revolutionary War period, with current inhabitants speaking a dialect of the English language unheard elsewhere. My father always said with conviction that it was Shakespearean— held over from the Colonial period—while some linguists link it to Cornwall, though most just believe it’s simply the result of longstanding isolation. Sea level rise from climate change threatens the island, with its land mass rapidly diminishing. Recent reports give no more than decades before overwash with the inhabitants becoming the first US climate refugees. In 1966 while on our yearly family vacation on the river, my father drove us (mother, brother, me) to Reedville for a day cruise to Tangier. I recall a fairly small, open boat (not nearly the size of the current Tangier Island Cruise boat) and a choppy crossing. Seabirds circled while a passenger with a 35mm camera — lens cap still in place—snapped photos. I was young, shy, and could not bring myself to tell her (a youthful failure I regret to this day). The harbor dock was crowded with familiar steel mesh (don’t call it “chicken wire”) crab pots, and we soon made our way to Crockett’s Chesapeake House, then the primary restaurant on the island. They had long practiced a version of farm-to-table, or sea-to-table, as their soft shells were directly off the boat or out of the float. No middle-men. The meal which included hush puppies was served family-style, heaped high on the table. There was no awkwardness even though our “family” was composed of the folks who were on the boat. It was clear to me, even at a that age, that I was in a special place, somehow out of time— not back in the past, but also not fully in the mainland present. I’m certain we wandered about, though I don’t recall seeing any of the now-ubiquitous golf carts, and we soon found ourselves on a return voyage. It is a passage I would like to repeat one day soon (before it is too late) as I was too young then to appreciate the trip: it soon became a shorthand term with my brother for any negative family outing.

Rock had both an outside source and his own floats to supply us with the gift of fresh soft shells. I think today most people’s experience of them are from Asian restaurants— their batter and high-heat deep-fat frying produce something delicious. On the bay, the soft shells are usually just dusted with flour, salt and pepper, and sautéed in butter at a much lower temperature. Such a technique requires perfect ingredients— there is no hiding behind a spicy, deep-fried crust. At lunch, we would first be invited to a co-cola from the cooler in the porch. Rock’s was just like the one BB had at his Woodstock Esso station— an elevated insulated chest that opened from above to reveal 6 oz bottles bathed in frigid water. The opener (with a top catcher) was on the side, and we soon found ourselves near an old Formica table while Rock prepared the crabs, slapping them between two slices of Wonder bread. No further condiments were necessary and looking back I’m guessing catsup or any other sauce would have warranted immediate dismissal from the table. Wonder Bread and a soft shell was somehow a match made in heaven.

After he retired, my father found his way back to the river, building a small house on the Western branch of the Corrotoman. It looked out over a bluff down toward the Rappahannock and, sheltered by a spit of sand, was a small cove with a dock. He had two crab pots and a holding cage (no float for peelers). On my last visit before his death, we walked out the dock, hauled in a dozen Jimmies which he proceeded to steam in the set-up just off his deck. We were soon elbow-deep in crab, Old Bay, butter, and white vinegar. It wasn’t Rock’s (there was no Wonder bread or co-cola), but it was close—and better still, we were close.

Thinking about that old fish camp brings a nostalgia for lost flavors, one’s I can’t be sure I ever really tasted — even as my whole body insists I did. We speak today about transitions and loss—climate change and extinction—and at the same time, because of cultural mobility and global transportation, celebrate the many cuisines previously unavailable. I can go to a dozen international markets in my city which, unlike the old storefronts in my neighborhood, sell tastes unimagined. In that way, we live in a world of plenitude. But I lament the loss of those old flavors— shad roe in wax paper, sautéed soft shells on Wonder Bread. Maybe they are still with us, but I fear they are not.

T. Hugh Crawford